I was involved with a group putting together a system of witchcraft. When one of the people involved was talking about materials and methods the the system would teach early on, one practice that came up was the witches’ ladder.

I was fairly excited. Witches’ ladders were something I learned as a child but hadn’t seen addressed in NeoPagan books of magic and witchcraft. When I saw what was put together, I found it a bit disappointing. It wasn’t the witches’ ladder I was expecting. It seemed familiar to other people, so I assumed it was the common version of the witches’ ladder in modern witchcraft approaches. Now I’m not so sure. Looking up witches’ ladders turned up many different approaches and ideas. The historical examples line up with what I learned. A couple modern examples fit what others in the aforementioned group spoke of. Then, there were innovations which seemed to be variants of or combinations of, the two approaches I was aware of.

With the diversity of witches’ ladders, I can’t speak to what is the popular standard or where it came from. So, this post will just talk about a variety of options.

The version that I took to be the modern sort is an example of basic knot magic. A length of rope or cord is needed for it. Many instructions include that the rope should measure in a multiple of three, so 9 inches, 12 inches, 3 feet, etc. Some instructions recommend braiding three cords. Once you have the cord, tie nine knots into it. There are some variations with different numbers of knots. As you tie the knots, you visualize your intention and put energy into the cord. The spell might be performed by knotting the cord towards you, or away from you, with some instructions saying to begin with each end and alternate working towards the middle.

A popular incantation is used with the spell.

“By knot of one, the spell’s begun,

By knot of two, the spell’s come true,

By knot of three, thus shall it be,

By knot of four, it’s strengthened more,

By knot of five, so may it thrive,

By knot of six, the spell we fix,

By knot of seven, the Stars of heaven,

By knot of eight, the hand of fate,

By knot of nine, the thing is mine!”

There are, of course, variations of this incantation. The incantation itself is very common. Apparently, it was used in Deborah Harkness’s A Discovery of Witches novels. If I remember correctly, a version of this spell is included in the Cord Magic or Knot Magic section of the BAM; Doreen Valiente also includes a variation of it in Witchcraft for Tomorrow. In Valiente’s inclusion of it in Witchcraft for Tomorrow, again - assuming I remember correctly, she just describes it as an example of knot magic.

To me this is an example of knot magic. It’s one which was kind of exciting to me when I first learned it because lots of people and books mentioned knot magic. Knot magic was often presented as an old and simple form of magic. But, at least in the late nineties and early aughties, not a lot of books talked about it. So, it was cool seeing an example explained - especially an example which could be applied for just about any goal.

There are, potentially, some issues with this spell. Knots are usually used to bind something, and untying knots looses that something. So, focusing on your goal while binding it up may not be the most obvious symbolism for manifesting it, or at least it might be more applicable to some goals and not others.

The incantation is nice and catchy, but the words don’t actually follow a structure for building towards manifestation. By the second knot we’re saying we’ve completed the goal, so why are the knots and words continuing? Three and six kind of reiterate this sentiment. That kind of positive claiming it into being is not uncommon. It might just make more sense to place towards the end. The spell references, but doesn’t necessarily clearly call upon, external powers - the stars of heaven, and the hands of fate - but it does that at the end rather than calling on that power at the beginning and winding or weaving it into the spell to build towards the manifestation.

Still, it’s a popular spell, so it probably works well for people.

Another modern variation seems to be the idea that a witches’ ladder is a sort of rosary for witches. This version either has thirteen or forty knots. Sometimes it’s made with beads. The knots or beads are touched as a way of counting or keeping track of chants, mantras for meditation, or short incantations and statements of intention. Some people link this to initiation cords as well. In either case, there doesn’t seem to be a link to the historical witches’ ladder.

According to blogger Nicole Canfield, Doreen Valiente describes the witches’ ladder in her dictionary of witchcraft, ABCs of Witchcraft. There Valiente says the witches’ ladder was a protection against the evil eye. The braided and knotted rope would catch and draw up the ill intentions of curses. These kinds of house protection charms are ubiquitous in folk magic. Those purposes don’t seem to be suggested by the historical examples of witches’ ladders.

Historical witches’ ladders have a few more physical pieces, but we don’t know anything about the incantations involved. We can guess as to their purposes, and there are some historical examples that have been found, researchers and historians have some ideas about why they might have been used. For the most part, they are similar to the three variations with which I’m familiar.

Typically, the historical ladders are usually strings with feathers. The Wellington Witch’s Ladder was discovered in a house in 1878. According to Canfield, the men who found it believed witches used it to climb back and forth between houses. This fits with superstitions that witches would flight through the night like the ill wind and enter houses to despoil things. The Wellington example used chicken feathers.

Canfield also explains that in Etruscan Roman Remains Leland recounts the story of talking with an Italian woman who explained “the witches’ garland” or “the spell of the black hen,” when he showed her a picture of a witches’ ladder which had been presented in a folklore journal in England. Here is what Leland says:

“In the year 1886 there was found in the belfry of a church in England a curious object of which all that could be learned at first was from the authority of an old woman and that it was called a witch's ladder. An engraving of it was published in the Folk-Lore Journal, and several contributors soon explained its use. It consisted of a cord tied in knots at regular intervals, and in every knot the feather of a fowl had been inserted.

I was in Italy when I saw this engraving, and read that the real nature of the object had not been ascertained. I remarked that I would soon find it out, which I did, and that most unexpectedly. For by mere chance, the very first Italian woman with whom I conversed, being asked if she knew any stories about witches, began with the following:--

"Si. There was in Florence four years ago a child which was bewitched. It pined away. The parents took it to all the shrines in vain, and it died.

"Some time after something hard was felt in the bed on which the child had slept. They opened the bed and found what is called a guirlanda delle strege, or witches' garland. It is made by taking a cord and tying knots in it. While doing this pluck feathers one by one from a living hen, and stick them into the knots, uttering a malediction with every one. There was also found in the bed the figure of a hen made of stuff (cotton or the like)."

The next day I showed the woman the engraving of the witch-ladder in the Folk-Lore Journal. She was astonished, and said, "Why that is la guirlanda delle strege which I described yesterday." I did not pay any attention at the time to what was said of the image of a cock or hen being found with the knotted cord, but I have since ascertained that it formed the most important part of the whole incantation.”

Leland goes on to present the spell, which he said was very difficult to procure because it was considered very dangerous and evil. The rest of the spell involves making a stuffed effigy of a hen, which seems to be a key part of the Italian variety in Leland’s description, but is not particularly relevant to our exploration.

Returning to the Wellington ladder, Chris Wingfield in “Witches’ Ladder: The Hidden History” says that on the museum display label, the purpose of stealing milk from a neighbor’s cow is listed. This is also in keeping with traditional ideas about witchcraft, and is not far off from the ladders we’ll discuss. Wingfield says the purpose for the ladder was included in a note from Anna Tylor when she donated the ladder, but seems to have originally been provided as speculation by James Frazer. Frazer based this assertion on folklore in Scotland and Germany.

Leland makes note of this ladder, explaining that Edward Tylor had displayed it in an 1891 Folklore Congress. It may have been the same one which Leland showed to his Italian informant.

Wingfield further explains that the meaning of the ladder was not originally clear to those studying it. He notes that Abraham Colles, who wrote - possibly with Tylor’s help - the article about the artifact that appeared in the Folklore Journal, noted that old women in the area referenced “a rope with feathers,” in conjunction with witchcraft, and that the men who found it immediately recognized it as a witches’ ladder. So, the concept was well known in the folklore of Somerset.

While those in Wellington seemed familiar with such things, Tylor was uncertain that they had thorough proof that the ladder was actually a magical device. Another folklorist, Sabine Baring-Gould corresponded with Tylor regarding the ladder. According to Wingfield, Baring-Gould of Devon spoke with a local woman, thought to be a witch in the 1890s, about the ladder. This woman was entirely unfamiliar with them and thought it was likely simply a tool for scaring chickens.

Wikipedia also talks about the historical sources for witches ladders, and notes the Wellington ladder, Baring-Gould’s fictional description of one, and Leland’s account. So it would seem, almost all our historical examples are just the Wellington ladder. That said, a second item of similar appearance was in Tylor’s possession. Additionally, as we noted, Leland claims to have had two in his possession as well. It’s possible that only one ever survived as an historical example, or there may have been as many as four.

Whether these witches' ladders were real or not, variations of the concept have become part of magic as it exists today. The term has, for some, given its name to basic knot spells as described above. Variations closer to the Wellington ladder have also made their way into modern folklore and magic.

The Wellington ladder is likely what inspired the versions of the witches ladder with which I was familiar.

To me, the ladder is a type of fetish used for the transfer of power. It can be built as a way to draw power from natural sources, to draw power from another magician or person, or a way to inflict harmful power on another person.

In the most basic instance, a cord is knotted with natural items tied into the knots. The knots might hold feathers, bones, shells, animal hairs, or plants. These items connect to the source from which they were drawn, or the overall spirits which oversee them and their kind. The knots bind some of their power into the charm. A link to the witch casting the spell is tied in the final knot. This could be done moving up the cord towards the witch or down the cord towards the witch based on whether you prefer building up or drawing down the power.

The natural items need to be awakened before tying them into the ladder. This can be done by speaking with them and offering them a sprinkling of water, suffumigating them with incense, consecrating them with candle light or a combination of these actions. Special spells and incantations calling upon divine powers to recognize or bless the life in them can be used as well.

As the items are knotted into the ladder, you can speak with them and their spirits and instruct them to lend their power to the ladder and therefore the one who it is made for. Alternatively you can design an incantation for that purpose.

The ladder should be placed in a special, safe place, to add power to the witch, or can be held, worn, or carried when working magic to more directly apply its power.

If the intention is to take power from another, the process is similar. Instead of using natural objects, as much as possible, use objects either belonging to, having been touched or worn by, or symbolizing the person from whom life, vitality, or magical power is to be taken. Similarly to the other form of the ladder, the items need to be awoken and instructed. If the items are “part of” the person from whom you are stealing power, simply instructing them to give over that power might not be something they will readily do.

You can take one of three approaches. Regardless of the approach, the items need to be woken up, just like awakening the natural materials. A spell of command can be used to force them to give over their life and power and sap it from their source. The items can be sweet-talked and convinced to give the power over, either as if it is what is necessary for their source or because the items have been left by their source and you have rescued them. An incantation could also be used to command the rope to forcibly take the power from, and through the items. The rope should be enchanted as each knot is tied regardless of which method is used.

This might sound like a very nasty thing to do, but it is a very traditional sort of witchcraft. Historical witches have many features which are similar to “dark shamans” or beings with spirit flight capabilities who feed from the spiritual power and life of other people and animals in their communities. European witches were also frequently known for stealing the potency from dyes and alcoholic beverages, or the milk from cows and the fertility from fields, and even from other people.

As noted above, James Frazer believed the purpose of the witches’ ladder was stealing milk from cows. Other commenters have noted that witches ladders create pining and wasting sickness. Canfield quotes Montague Summers who described a witches ladder in connection with the “Island-Magee” witch trial. This trial in 1711 was the last, or one of the last, Irish witch trials. A Mrs. Haltridge claimed that Mary Dunbar was showing signs of demonic possession. Dunbar accused eight women of attacking her in spectral form. Some historians have suggested that Dunbar was aware of accounts from Salem Massachusetts and mimicked the behaviors described in stories of Salem. The records of the trial and its results may have been destroyed, and so details don’t survive. Summers claims that during the investigations of the bewitchment, an apron to Mary Dunbar had been discovered. Summers may not be a reliable account as he claims Dunbar was a guest visiting the bewitched, whereas it seems she was the key bewitched individual. According to Summers, Dunbar’s apron had been tied up with string, and the string had been knotted with nine knots. The string was tied into the folds to make it difficult to remove, and when the apron was bewitched it had caused Dunbar to have seizures and fits and was sickened almost to death.

According to Summers, witches’ ladders were a common means of cursing and were made by tying knots in a cord while reciting “horrid maledictions,” and then hiding it in a secret place. The intention, according to Summers, was to cause the target to “pine and die.”

Prior to Summers, Sabine Baring-Gould included a witches’ ladder in his novel Curgenven. Baring-Gould’s fictional witches ladder was a tool of cursing, and operated by rotting away to release the ill intentions held within the ladder to impact their target. Baring-Gould explained to Tylor that he had no source for his ladder aside from his own imagination and the inspiration from the Wellington ladder. Baring-Gould’s example is interesting though because the ladder is made from three colors of thread, black, brown and white. Otherwise, it was similar to the Wellington ladder, but had a stone tied to the end so that it would sink into a pond to rot as it released its evil magic.

The last sort I am aware of is for cursing, like Baring-Gould and Summers described. Unlike the previous example, which could be compared to the wasting sickness Summers describes as it saps power, or life, or health, from someone, this one asserts ill intention upon the target to bring about harm.

Some of the accounts of ladders describe the knots being made and then the feathers being inserted into the knots. That is the method you will use when using a ladder to curse someone. The rope should be baptised as the target. A physical link should be awakened and tied within the rope prior to the baptism. Then knots are tied into the rope with the negative intentions forced into the rope with each knot, and incantations spoken to bind pain, discomfort, and whatever other ill effects are desired into the target. You could use feathers like in Leland’s Black Hen spell, but I would use pins. The pins should be baptised as whatever ill fate, or ill force is intended to pierce the target. The water can be fixed with herbs and incantations beforehand to add to imparting the intended nature to the pins. The pins can be heated in a candle’s flame or a fire, particularly one with candles or incense which has been consecrated and has the nature of the intended outcome of the curse. The pins should then be stuck into each knot with an incantation as one does so.

Once the cursing ladder is finished, it should be hidden. It could be hidden in a safe place convenient to the magician. Like most curses, it would be more effective to hide it on the property of the cursed, or within their clothing, or on their person.

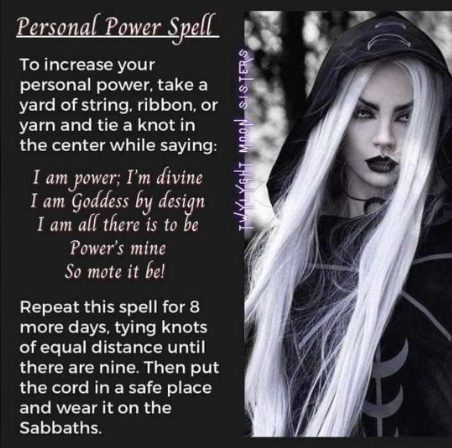

To bring things back full circle, I saw a spell meme the other day that is based on the 9-knot spell but intended to build a power source for the witch. That puts it between the modern 9-knot version of the ladder and the more traditional ladder which draws power for the witch.

“To increase your personal power take a yard of string, ribbon or yarn, and tie a knot in the center while saying ‘I am power, I’m divine, I am Goddess by design, I am all there is to be power is mine, So mote it be.’ Repeat this spell for eight more days, tying knots of equal distance until there are nine. Then put the cord in a safe place and wear it on Sabbaths.”

The spell is…kind of awful. The idea is good though.

The incantation doesn’t call upon any source of power or draw power for anything to increase the power the witch has access to. The witch just makes a couple empty statements about how powerful they are. They don’t structure the incantation to build power, draw power, or invoke power from anything. “Divine,” “Goddess,” “All,” these are all things that the witch could draw on and aspect with a more thorough incantation or invocation. Then having called on that power, the power could be bound into the cord to be used in the future.

Typically though, these kind of knotting something into a cord for future use spells involve untying the knots when you want to use it. A traditional example of this is tying knots to capture the force of the wind and calm it, and then untying the knots to release the force and raise winds.

Since the knots aren’t holding things to draw power from, and then conducting it into a link to the witch, a spell like the one presented above would make more sense if the power was knotted into the cord and released by untying. Increasing your power would also be easier by drawing power from elsewhere. I won’t get into the aesthetic choice that is that incantation…

Criticisms aside, the idea obviously connects with concepts that we see in folklore and which seem to be part of old witchcraft. Using knots to build a fetish or charm meant to increase power is solid. The approach of the witches ladder might make more sense than the type of approach presented in the meme. But, the witches ladder involves a much more engaged and enspirited use of material than the meme. Similarly, in comparing the nine knot spell as a version of “witches’ ladder” to the historical examples or the versions with which I was familiar, the difference again is the use of enspirited materials.

Lots of kinds of magic can work, though. You should do the kind that is well suited to you, your situations and your needs. You have to do the magic that is suited to the materials you have access to. Your preferences matter. You might find that the effects are different based on the type of approach used, so it may be worth experimenting with one if you’ve only tried the other.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this please like, follow, and share on your favorite social media!. You can also visit our Support page for ideas if you want to help out with keeping our various projects going. Or follow any of the links below.

We can be followed for updates on Facebook.

Check out my newest book, Familiar Unto Me: Witches Sorcerers and Their Spirit Companions

If you’re curious about starting conjuration pick up my book – Luminarium: A Grimoire of Cunning Conjuration

If you want some help exploring the vast world of spirits check out my first book – Living Spirits: A Guide to Magic in a World of Spirits

NEW CLASS AVAILABLE: The Why and What of Abramelin

Class Available: An Audio Class and collection of texts on the Paracelsian Elementals

More Opportunities for Support and Classes will show up at Ko-Fi

I'm of the school of thought that knot magic is about binding or saving for later.

ReplyDeleteWhen Tau (a mutural friend of BJ and mine, for folks reading along) was entering another pregnancy after a miscarriage I did a braided cord spell to 'tie the pregnancy in place'. After she reached 38 weeks, I undid the braid for an easy delivery.

I did this based on folk magic mentioned (and followed) by a then co-worker who kept braids in her hair during her pregnancy but undid them before her due date. It was a family tradition.

It didn't help with the easy delivery in her case, tho'. She ended up needing a c-section.

Super well written, this is a great handbook for knot magic.

ReplyDelete